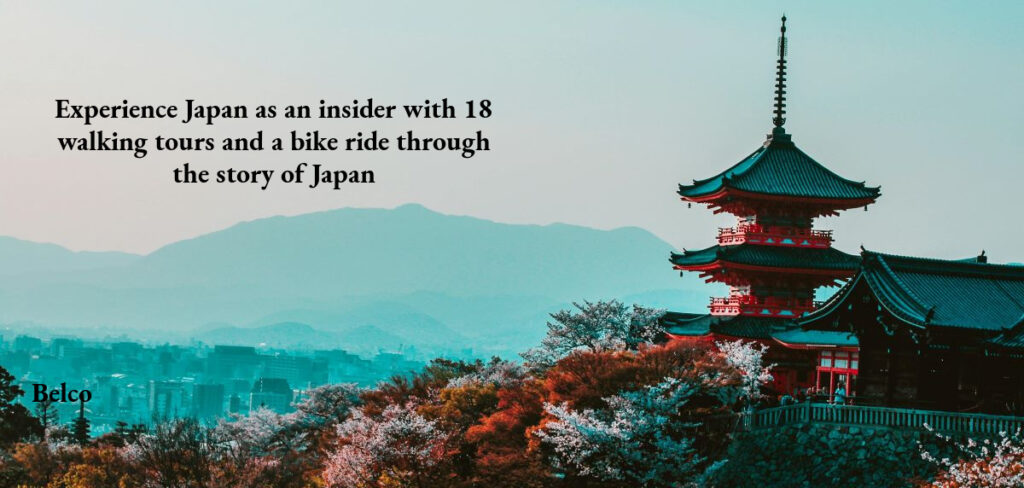

Explore Japan as an insider with this unconventional guide that tells the stories of the people and events that make the places special to the Japanese.

Recent reviews

“We’re planning our first trip to Japan and have amassed a whole library of travel guides, maps, websites, and even an in-country guide. But nothing in this collection begins to touch the fascinating history of people and places that Dr. Doe brings to life in her 19 Great Places That Tell the Story of Japan. I Highly recommend this book.” Susan C.

“Essential companion for the independent traveler who wants a deeper understanding of Japan.” Catharine S.

“I just finished reading this terrific new book and loved it! It fascinatingly lays out Japan’s history and provides useful details on transit and access to sites.” Geoff H.

A word from the author

This book is the guide I wish I’d had when I first came to Japan, and always wanted to know more about what I was seeing. Only years later did I learn just how much I had missed.

what i

Dr. Doe studied Japanese literature at Japan Women’s University in Tokyo, and taught classical Japanese at Stanford University. She’s the author of A Warbler’s Song in the Dusk, a study of the life and work of the eighth-century Japanese poet Otomo Yakamochi, from University of California press. She also had a surprising second second career covering the Japanese semiconductor industry for Electronic Materials Report, Solid State Technology Magazine, and Wafer News, and working for the trade group SEMI.

Latest Posts

Making Sense of Japan’s Shrines and Temples: A quick scenic tour through Shinto and Buddhism in Japan

Takachiho: Early Shinto

The early Japanese worshipped ancestral native spirits who dwelt on the sacred mountains and in other special places. They did not make images of these spirit gods, but they built simple wooden shrine houses for them, and passed on oral tales of the adventures of these deities who created and settled Japan. The most important of these deities was the Sun Goddess, who once became so angry at the other gods that she retreated to a cave, plunging the world into darkness. The other gods eventually lured her out by the irresistible sound of their lively dancing, to restore light to the world. The clan that claimed descent from this Sun goddess became the leading Shinto priests who performed the prayers to protect the country, and eventually became the emperors of Japan.

Asuka: Contact with Korean kingdoms transforms Japan

/

H

The scenic rural Asuka area, outside Nara, is famously the ancient heartland of Japan, once dense with palaces and temples. Here contact with the neighboring Korean kingdoms transformed Japan in the 500s-600s, introducing better weapons, written language, a model for imperial government to control the country, and the continental religion of Buddhism. It’s also one of the best places to get out into the Japanese countryside, as the area is now a historical park, with bike rentals by the station and trails through the fields, among ancient tomb mounds and small museums of relics of the Asuka era.

Soga clan builds first major Buddhist temple

In fhe 500s a Korean king seeking military aid sent Japan’s emperor in Asuka the gift of a Buddhist statue, with a note that this powerful god would grant all prayers. As the emperor was the chief priest of native Shinto, he banned the foreign religion for fear it would anger the native gods. However he did allow the Soga clan, who were close to the Koreans in Japan, to try worshiping the statue privately. The leader of the Soga later prayed to these foreign gods for help in defeating the Shinto priests for control of the government. After his victory, he built Japan’s first major Buddhist temple complex in thanks. The small temple of Asuka-dera remaining on the site today features Japan’s oldest extant Buddha statue, a large image of the Historical Buddha cast in expensive bronze, a display of the Soga wealth, and their close connection with skilled Korean craftsmen.

This statue is of the Historical Buddha, a prince who lived in India somewhere around 400-500 B.C. Distressed by all the suffering he saw outside his palace, the prince went in search of understanding. After trying different religious practices and ascetic disciplines, he at last reached enlightenment while meditating. He realized that human life always included suffering, that suffering was caused by worldly desires, and that people could escape suffering and reach enlightenment by a disciplined life of meditation and right actions. The statue’s earlobes are elongated from the prince pulling off his jeweled earrings when he left his palace.

Horyu-ji : Emperor gives support to Buddhism

Off in a quiet suburb of Nara, often missed by foreign tourists, the World Heritage monastery of Horyuji is one of Japan’s most interesting temples, remarkably preserved from the 600s. Here Prince Shotoku first put the full wealth and prestige of the imperial government into building a great monastery, with the best art and architecture of the day, to train monks for Japan. Shotoku himself became worshiped as a founding saint of Japanese Buddhism, which has helped to keep his temple an active religious organization for more than 1000 years.

One of Shotoku’s first acts as regent was to offer a statue of the Healing Buddha in prayer for his father’s recovery from illness, as his father had requested. As Shotoku’s father was the emperor and the chief priest of Shinto, the court was horrified that he would dare to anger the Shinto gods by making a prayer offering to a foreign deity. However, Shotoku’s Soga clan now controlled the government, so Shotoku could build an imperial temple complex to promote his family’s faith.

Tree rings indicate the tree for the great central pillar of Horyuji’s pagoda was cut in 594, and the temple’s central buildings and its tile-roofed mud walls were built just slightly later–and remain little changed today. The wooden pagoda and worship hall in the central courtyard with elaborate brackets gracefully supporting the heavy tile roofs, are one of the very few surviving examples of the sophisticated Tang Chinese wooden architecture of the era. The temple’s worship hall houses the family statues, including the controversial Buddha of healing that Shotoku offered for his father, and a statue of Shotoku as an emanation of the Buddha, offered by his son. The temple museum features a great collection of Japanese art of from the 600s

Nara: Japan’s first city

Nara was Japan’s first permanent city, built in the 700s as the grand new capital for the growing central government, one of whose main roles was to perform the Buddhist religious rituals to protect the country. This wealthy imperial city was modeled after the great Tang Chinese capital of Chang-an, with a grid of wide avenues and Chinese-style vermillion temples. The Todaiji temple’s museum, and that of neighboring Kohfuku-ji temple, preserve a wealth of Chinese-style Buddhist sculpture, making clear how closely Nara was connected to its neighbors on the continent.

Todai-ji: State Buddhism

The emperor built Nara’s grand temple of Todaiji to house his five-story statue of the Buddha, a national prayer offering to end an epidemic ravaging the country. This statue is not the Historical Buddha worshiped in Asuka, but the Universal Buddha Dainichi, from whom all the myriad Buddhas emanate, a more recent import from China that better emphasized that all power emanated from the central imperial government. The emperor also had a sub-temple of Todaiji built in in every province of Japan to spread the faith and connect the provinces to the national mother church.

Casting this giant metal statue was a major technical achievement for the 700s–and a display of the remarkable national power of Japan’s young Chinese-style imperial government. Temple records say some two million workers worked on the project, carrying 500 tons of copper and seven tons of beeswax to Nara from across the country for the lost-wax casting. Much of the work was done by the corvee labor of people paying their annual taxes for their land.

Nara Deer Park: Buddhist city forbids killing of animals

Nara’s famous deer freely roam the religious city, which features a sacred preserve where killing of animals is forbidden, as a first commandment of Buddhism is to kill no living thing. The Nara Deer Park is modeled on the famous Deer Park of Sarnath, India, where the Historical Buddha reached enlightenment, and found his first disciples among its community of holy men. Nara’s Shinto shrine also views these deer as sacred messengers from the gods. Early visitors to Nara saw meeting one of these deer from gods as a great blessing, and the shrine began to feed them to draw them down from the forest to encourage more such meetings. Shrine priests now now care for a herd of about a thousand sacred deer. Harming one of these protected animals has severe legal penalties.

Kasuga Shrine: Native Shinto continues to flourish

While the court enthusiastically adopted Buddhism, it also continued to support native Shinto. The same family that built Kohfuku-ji temple to worship its Buddhist statues also built Kasuga shrine to worship its ancestral Shinto deities. The shrine is one of Japan’s oldest and most lovely, set within an ancient forest where tame deer roam.

The shrine maintains the early Shinto practice of worshipping the sacred mountain where the gods reside. gods. People today still come to Kasuga and other Shinto shrines today to pray to the ancient gods of fertility for the safe birth of healthy children, and other issues of love and marriage. Shrine priests also do a busy business performing ceremonies to bless happy new beginnings, from new marriages and new babies to new businesses and new cars.

Buddhism, in contrast, offers guidance for living, gods for curing illness, and deities for help in other times of need. Temple monks perform memorial services, burials, and prayers for the souls of the dead. Many Japanese turn to both shrines and temples as needed.

Toji temple: New Shingon ritual Buddhism for new capital of Kyoto

Nara’s academic temples grew so wealthy and powerful by the 800s that they began to threaten the imperial government itself, so the emperor moved the capital off to the Kyoto area, to build a new city where he could ban the old temples and escape the meddling monks. New religious leaders who had studied the latest versions of Buddhism in China stepped in to fill the need for prayers and healing in this new city without temples. Chief among these was the monk Kukai, who came down from his retreat in the mountains to cure the emperor’s illness with dramatic new rituals with fierce deities, drums, fires, and chanting in Sanskrit. The emperor put Kukai in charge of building a new national temple for Kyoto at To-ji , to perform his rituals to protect the country. To-ji today remains little changed from more than 1000 years ago, with a crowd of fierce new deities from China that provide an immersive three-dimensional mandala for meditation, and a dramatic setting for magical rituals.

/

While the Nara Buddhism largely involved people donating statues in prayer, and monks studying ancient sutra texts in hopes of eventually reaching enlightenment after many incarnations, Kukai instead taught that anyone could cultivate the Buddha nature within by disciplined meditation and rituals to escape attachment to worldly things and potentially achieve enlightenment in this lifetime.

Kukai passed his secret rituals only on to the elite men who were his disciples, so his Shingon sect remained primarily a religion of the nobility. However, Kukai’s ideas on the value of personal disciplined practice had a wide influence on the rest of Japanese Buddhism. Kukai also famously started Japan’s first school for commoners, and is credited with developing Japan’s kana syllabary from his familiarity with syllabic Sanskrit script he studied in China, so ordinary people could read and write without having to learn Chinese characters.

Mt. Koya: Kukai and his followers await the Buddha of the future

When Kukai eventually passed away while meditating, his body miraculously did not decay, and he continues to sit in eternal meditation at his grave on Mt. Koya, to await the coming of the Buddha of the Future. Monks continue to serve him a ceremonial breakfast here each morning. Many of Kukai’s followers wanted to wait near him when they died, so the vast Oku-no-in cemetery grew up around his grave in a stunning cedar forest on Mt. Koya.

Today Shingon temples often feature a statue of the fierce deity Fudo, and frequently perform dramatic fire rituals where wooden prayer boards are sent on smoke to the gods. Many faithful also make Kukai’s pilgrimage around the 88 temples of Shikoku.

Fushimi Inari Shrine: Kyoto prays to the God of Rice

When the emperor had Kukai build the Kyoto national temple for prayers for the country, he also ordered the construction of the Fushimi Inari Shrine, to pray particularly to the god of rice for good harvests, on which the country depended. With its photogenic tunnels of orange tori gates, the shrine has remained an active religious site for more than 1000 years. All of its hundreds of torii gates were offered with donations in prayer for success in business, many of them by Japan’s leading corporations today. The shrine priests continue to perform the traditional rituals for every stage of the vital rice crop on which Japan still depends.

Mt. Hiei: Tendai Mountain discipline

The scenic mountain monastery of Enryaku-ji is a great day trip from Kyoto, an adventure by train, cable car and ropeway through the treetops. Looking down on the city far below on one side, and Lake Biwa on the other, one feels one has left the mundane world behind. This mountain is believed to protect Kyoto from evil from the dangerous northeast direction, so the emperor supported monks there to offer prayers to protect the city. This imperially supported monastery grew into Japan’s most powerful religious institution, a vast monastery complex in the forest which has trained almost all of Japan’s monks since the 800s.

Enryaku-ji’s Tendai sect was the religion of the emperors, and the powerful temple pressured the emperors to banish competing preachers it didn’t like. It also regularly sent its own army of warrior monks down to Kyoto to burn the temples of its rivals. Tendai teachings center on the classic Lotus Sutra, with its stories of the merciful Kannon who helps people in myriad ways. Tendai today takes a wide view that many different practices are all part of one Buddhism, so it now honors the monks who went on to found other sects that it once persecuted, and Tendai monks now chant to Amida as well as perform esoteric rituals.

Japanese monks and Shinto practitioners had long retreated into the mountains to live austerely for periods to rid themselves of worldly desires, and the isolated mountain monastery of Enryaku-ji continues this tradition today. The temple is known today for its Marathon Monks, a select few who become national heroes for completing its extremely difficult 1000-day running challenge. It also expects all its monks to discipline their minds to do difficult things. Enraku-ji monks in training must spend many days chanting continuously without stopping or sitting. All monks who hope to advance in rank must complete a 100-day running challenge, rising in the wee hours run 20 miles each night, offering prayers at dozens of places along the way, before starting their regular work day at 6am.

Byodo-in: Salvation by faith in Amida Buddha

Byodo-in temple, just outside Kyoto in Uji, features a famous Amida Buddha surrounded by angelic musicians floating on clouds, suggesting the paradise where Amida will welcome all who have faith in him when they die. A saying of the time was that a visit to the beautiful Byodo-in would make anyone a believer in Amida’s paradise.

In the 1000s, the Kyoto courtiers believed that Buddhism was in the period of decline predicted by the sutras, when people could no longer achieve enlightenment by their own efforts alone. Along with traditional Buddhist practice, people must also have faith in Amida Buddha, who would welcome all who had faith in him to his Pure Land paradise after death. Amida’s salvation by faith, however, had many different levels, and one’s behavior in life still determined the level one would be assigned after death, so people still needed to keep up other Buddhist practices. Still, This new idea of salvation primarily by faith, not works, opened Buddhism to more people among the elite, especially to women, who no longer had to first be reborn as men.

Sanjusangendo: Emperor’s lavish temple spending leads to samurai takeover

The spectacular array of 1001 life-sized golden statues of the merciful Bodhisattva Kannon in the Kyoto temple of Sanjusangendo was the emperor’s extravagant prayer offering for the success of his reign. The huge expense of this private chapel suggests that the old Buddhism of donations for merit by the rich was ripe for replacement by new types of Buddhism more accessible for ordinary people.

This costly imperial temple ended up being the emperor’s undoing. Samurai in the provinces were gaining control of the old nobility’s income estates in the countryside, leaving the emperor short of funds to pay for his lavish chapel. His samurai general stepped in to pay for the project, and the emperor rewarded his benefactor with a high rank at court—something never before granted to a commoner. This samurai Kiyomori of the Heike clan then managed to seize control of the government. He packed the court with his clan members, deposed the emperor, married his daughter to the new emperor, and when the royal couple had a son, took over rule of the country as regent for the boy. Other samurai clans soon defeated the Heike to seize control of the country, and moved their new government far away from the old Kyoto court, to rule from their new military capital of Kamakura, near Tokyo.

Honen-in: Honen preaches Pure Land Buddhism for ordinary people

theHonen-in: Honen’s Pure Land salvation by faith alone

In the 1100s the monk Honen taught a more radical version of salvation by faith in a rough shelter at Honen-in on the outskirts of Kyoto, as he was banned from preaching within the city. While worship of Amida Buddha had long been just one part of Buddhist practice, Honen taught that since Amida Buddha had vowed to save all people who had faith in him, faith in Amida was the only thing that mattered. All other Buddhist practices, including living a monastic life or making donations in prayer, were useless. Powerful Enryaku-ji was threatened by this heresy and had the emperor banish Honen to the provinces, where he spread his teachings more widely. Honen’s controversial teaching of salvation by faith alone opened Buddhist salvation to ordinary people. His Pure Land sect became widely popular with both commoners and samurai, and remains Japan’s largest denomination today.

Chion-in: Busy head temple of Pure Land

Chion-in’s great gate looks more like a castle than a temple, but the new Tokugawa samurai rulers in the 1600s were Pure Land believers themselves, and rebuilt Chion-in as their family temple and base in Kyoto. They likely also used the great gate as their military lookout over the city. The temple proudly displays its connection with the rulers, still displaying the Tokugawa three-leaf crest many places around the temple.

Today the active temple is one of the best places to see something of living contemporary Buddhism. Believers come from around the country to join the chanting procession each morning for an hour at first light, attend the daily mid-morning service, offer prayers at Honen’s grave, and attend a full schedule of lectures and memorial services.

Ryoan-ji: Zen abstract garden for meditation

At around the same time that Honen introduced his Pure Land sect of salvation by faith alone for all believers, the monk Eisai returned from studying in China to introduce Zen to Japan, preaching a simple life of disciplined meditation that could potentially lead anyone to enlightenment in this life. Enryaku-ji had him banished from Kyoto for these teachings, but the samurai appreciated the power of discipline, and welcomed him to their new capital in Kamakura. Zen temples typically feature statues not of exotic deities, but of human religious leaders, from the Historical Buddha to the temple’s famous teachers. Zen temples also often have minimalist abstract gardens and ink paintings to help calm and clear the mind for meditation. Ryoanji was among to first of these temples to arrange its sand and rocks not as a miniature landscape, but as a more abstract metaphor. While the abstract garden has many abstract interpretations, temple records say it depicts a fierce monk leading his cubs across the water of delusion towards enlightenment, like other rock gardens of the day.

Ankokuron-ji: Nichiren preaches chanting to the Lotus Sutra

In the 1200s, the monk Nichiren came to the Kamakura capital to preach his belief that the only right religion was to chant one’s reliance on the Lotus Sutra, which would both improve one’s life and improve the world. He presented a manifesto the government urging it to ban all other religious practices besides his, as all other sects were not simply useless but actually spread evil in the world. Kamakura’s rulers paid no attention, but angry monks and lay believers tried to run Nichiren out of town. The government then banned his preaching and exiled him several times, but Nichiren kept coming back to preach Finally the government decided to execute him, but at the last minute, a miraculous great light appeared in the sky and terrified the executioner into sparing him. Nichiren then left Kamakura for good, but continued to write and preach. His Nichren sect eventually grew into one of Japan’s largest, with some 10 million followers today. Its lay organization Soka Gakkai has adherents overseas, and formed one of Japan’s major political parties. The Nichiren religious sect has discommunicated the Soka Gakkai lay organization, but spawned several other offshoots. Nichiren temples typically feature a sacred hangng scroll with a dense pattern of calligraphy by Nichiren.

/

/